Buy your weekday smoothies and get your weekend ones for free. (7 for the price of 5!)

Vegetable glycerin has become one of the most commonly used carriers in modern herbalism. It is often promoted as gentle, natural, and alcohol-free, and is frequently positioned as the “safer” option for children, sensitive individuals, or anyone seeking a cleaner form of plant medicine.

But in herbal medicine—as in nutrition—what sounds gentler is not always what is more honest or more effective.

Our whole-body health should be approached with a simple guiding principle: the body is sacred, and healing should never depend on hidden tradeoffs. This article examines vegetable glycerin not through marketing language, but through physiology, extraction science, and long-term wellness discernment.

What Vegetable Glycerin Actually Is

Vegetable glycerin (also called glycerol) is a clear, odorless, sweet-tasting liquid produced by hydrolyzing plant oils—most commonly soy, palm, or coconut—into fatty acids and glycerol. Chemically, it is a sugar alcohol, not a fat, and not a whole-plant substance.

It is:

- Water-soluble

- Highly hygroscopic (it draws water to itself)

- Roughly 60% as sweet as table sugar

Glycerin is used widely in:

- Processed foods and syrups

- Pharmaceutical formulations

- Cosmetics and skincare

- Alcohol-free herbal extracts (glycerites)

It is classified as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) by the FDA. This designation, however, reflects acute toxicity—not suitability for daily medicinal use, metabolic impact, or extraction integrity.

The Metabolic Reality: Not as Neutral as It Appears

Vegetable glycerin is often described as “safe for blood sugar” because it does not spike glucose as sharply as refined sugars. This framing is incomplete and, for some individuals, misleading.

Once ingested, glycerin (glycerol) is processed in the liver and can be converted into glucose through a metabolic pathway called gluconeogenesis.

Gluconeogenesis is the body’s process of creating glucose from non-carbohydrate sources—such as amino acids, lactate, or glycerol—when dietary glucose is low. This pathway is essential for survival during fasting, but it is not metabolically neutral. When activated regularly, it still results in new glucose entering the bloodstream.

In the context of repeated medicinal dosing, this matters.

Regular use of glycerin-based extracts may:

- Gradually elevate blood glucose

- Trigger insulin release

- Disrupt glycemic stability over time

This is especially relevant for individuals with:

- Diabetes or prediabetes

- Insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome

- Chronic fatigue associated with blood sugar swings

For these individuals, a daily glycerite—often chosen under the assumption that it is “gentle” or “safe because it’s alcohol-free”—can quietly work against metabolic healing by repeatedly engaging glucose-producing pathways the body is already struggling to regulate.

Digestive Effects and Gut Stress

Glycerin’s hygroscopic nature is not incidental—it is pharmacologically active. By drawing water into the intestines, glycerin increases stool softness and motility, which is why it is used medically as a laxative.

When taken orally and repeatedly, glycerin can:

- Cause bloating and gas

- Loosen stools or provoke diarrhea

- Increase irritation in an inflamed gut

For individuals with:

- IBS

- Leaky gut

- Post-antibiotic dysbiosis

- Chronic digestive inflammation

...glycerin can add mechanical and osmotic stress to an already compromised system. In this context, "gentle" becomes a misnomer.

Microbial Stability: A Foundational Issue

One of alcohol’s oldest roles in herbalism is preservation. Ethanol is naturally antimicrobial. Vegetable glycerin is not.

Glycerin-based extracts:

- Do no reliably inhibit bacterial or fungal growth

- Are highly sensitive to water content

- Often require refrigeration

- Have shorter and less predictable shelf lives

From a medicinal standpoint, a preparation that depends on strict handling conditions to remain safe is inherently less resilient.

Traditional herbal systems understood this well. This is why glycerin was historically used sparingly, while alcohol became the backbone of stable, reliable medicine.

Extraction Integrity: What Glycerin Leaves Behind

Perhaps the most critical limitation of vegetable glycerin is its narrow extraction range.

Glycerin extracts water-soluble compounds such as:

- Mucilage

- Polysaccharides

- Tannins

- Certain glycosides

However, it performs poorly with many of the compounds responsible for deep therapeutic action, including:

- Alkaloids (key for nervous system support)

- Resins and oleoresins

- Terpenes and volatile aromatic compounds

- Fat-soluble sterols

The result is often an extract that tastes pleasant and feels soothing, but is medicinally incomplete. This should not be viewed as a minor technical detail. Incomplete extraction is a form of compromise, and compromise has no place in medicine meant for long-term healing.

Carrier Comparison at a Glance

| Carrier | Strengths | Limitations |

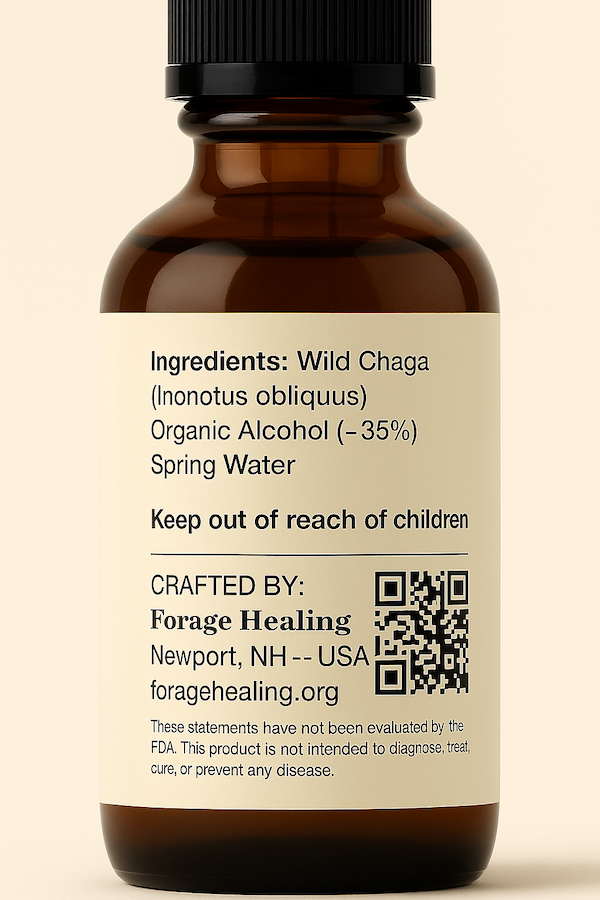

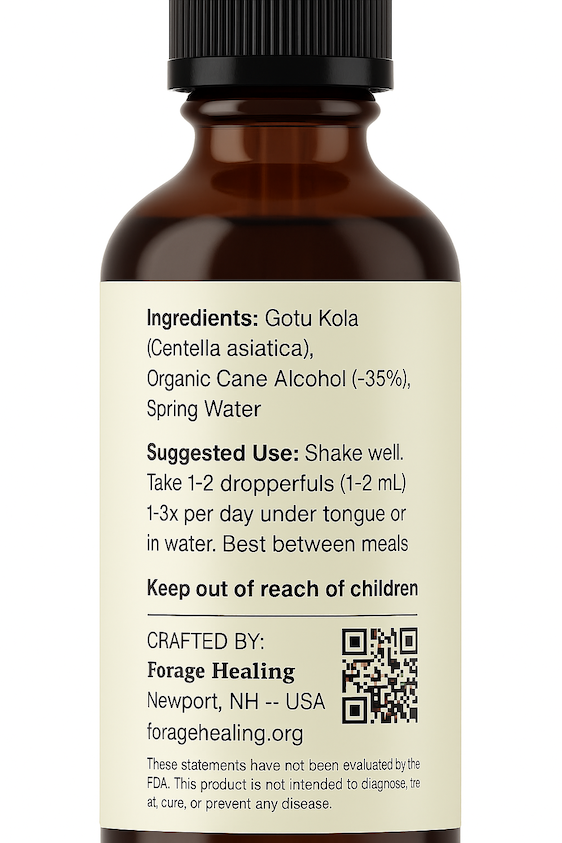

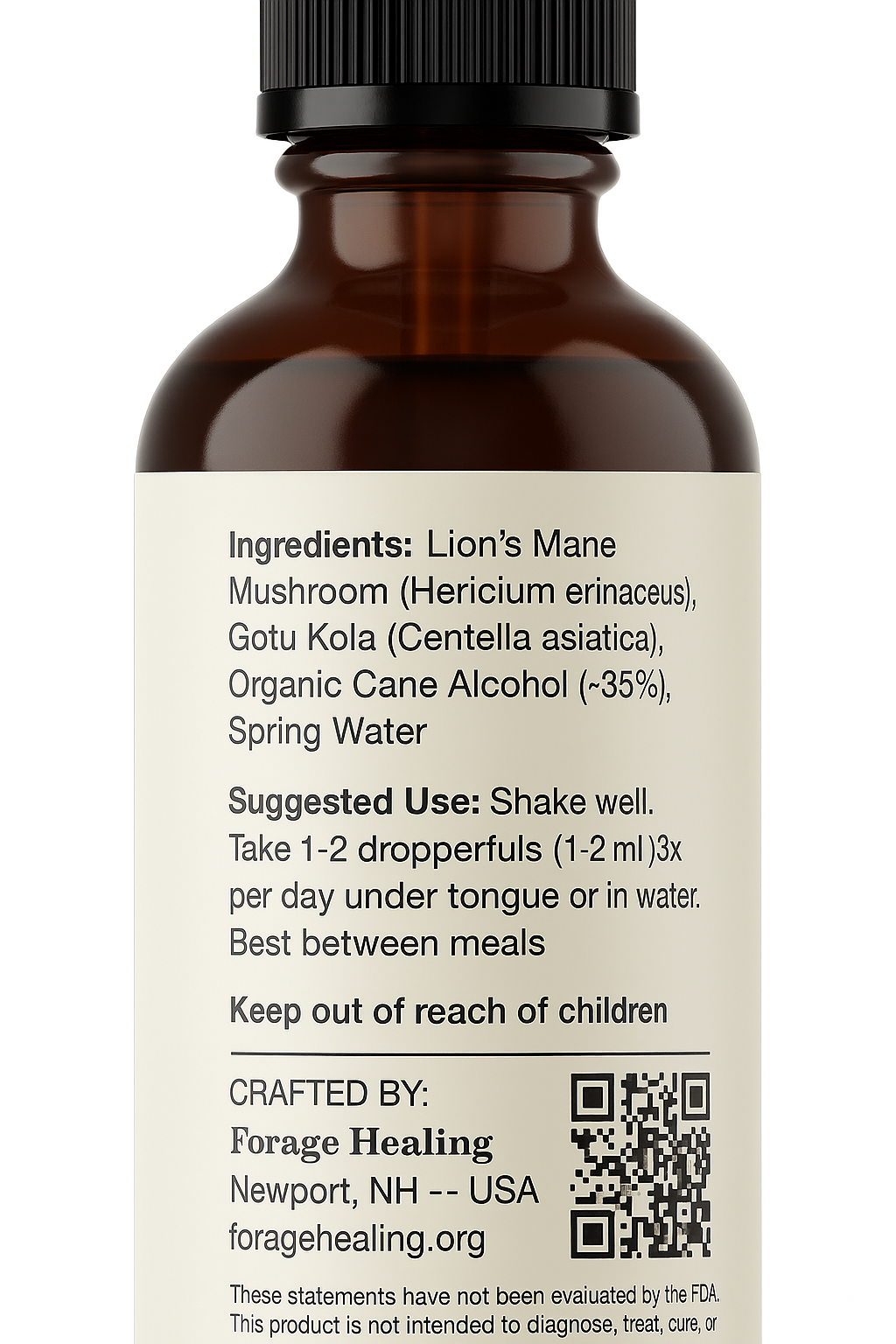

| Alcohol | Full-spectrum extraction, antimicrobial, stable | Taste, cultural or personal concerns |

| Vegetable Glycerin | Sweet, alcohol-free | Metabolic impact, weak extraction, microbial risk |

| Oil | Excellent for fat-soluble compounds | Narrow spectrum, short shelf life |

| Water | Simple and traditional | Spoils quickly, limited preservation |

Quality and Source Concerns

Most commercial vegetable glycerin is highly refined and industrially processed. The vast majority of it is derived from GMO soy or sustainably sourced palm oil unless explicitly stated otherwise.

This matters, because the source and processing of a carrier are not neutral.

GMO Soy and Soy-Derived Glycerin

Glycerin derived from soy—particularly genetically modified soy—is produced from crops that are routinely treated with glyphosate-based herbicides. While refined glycerin contains little to no protein, trace residues and the broader implications of industrial monocropping remain relevant for those seeking truly clean medicine.

Beyond genetic modification itself, soy presents additional concerns:

- Soy is one of the most common food allergens

- It contains phytoestrogens that may be problematic for hormonally sensitive individuals

- It is heavily associated with intensive chemical agriculture and soil depletion

For individuals pursuing herbal medicine as a path away from industrial food systems, a soy-derived carrier represents a philosophical and practical contradiction.

Palm Oil and Sustainability Concerns

Palm oil–derived glycerin presents a different but equally important set of issues.

Unless explicitly certified as sustainably sourced, palm oil production is strongly associated with:

- Large-scale deforestation

- Destruction of wildlife habitat

- Soil degradation and ecosystem loss

- Social and labor abuses in producing regions

For a medicine rooted in reverence for creation and stewardship of the earth, the use of unsustainably sourced palm oil conflicts directly with those values.

Why This Matters in Medicine

In medicine, the materials used to prepare a remedy are not incidental. Carriers influence not only extraction and stability, but also how a preparation interacts with the body over time.

Highly refined, industrially produced carriers—regardless of regulatory safety status—tend to move herbal medicine away from whole-system compatibility and toward isolated, engineered inputs. This shift is not inherently malicious, but it does warrant scrutiny when remedies are intended for repeated or long-term use.

When a carrier is derived from chemically intensive agriculture or requires extensive industrial refinement, it raises practical questions rather than ideological ones:

- How traceable is the ingredient back to its source?

- What metabolic pathways does it engage when used regularly?

- Does its production introduce unnecessary variables into a therapeutic context?

From a clinical and educational standpoint, these questions matter because medicine is cumulative. Small exposures, when repeated daily, shape outcomes over time.

For this reason, traditional herbal systems consistently favored carriers produced through simple, biologically familiar processes—such as fermentation—over those requiring extensive chemical transformation. This preference was less about ideology and more about reliability, predictability, and long-term tolerance.

Understanding carrier choice as part of the medicine itself allows practitioners and individuals to make more informed decisions, particularly when supporting metabolic health, hormonal regulation, or environmentally conscious practices.

Unless glycerin is:

- USP or pharmaceutical grade

- Certified non-GMO

- Sustainably sourced

- Transparently processed

...it may be far removed from the idea of whole-plant, or whole-body healing.

Clearing the Vaping Confusion

Some concerns about glycerin arise from research on inhalation, where heating glycerol can produce toxic compounds such as acrolein.

To be clear:

- This risk applies to heated inhalation

- It does not apply to oral herbal extracts

That said, the broader issue remains: glycerin is frequently assumed to be benign without sufficient consideration of dose, duration, and physiology.

Medicine Without Compromise

In any medicinal system, the effectiveness of a remedy depends not only on the plant itself, but on the medium used to prepare and deliver it. Carrier choice determines what compounds are extracted, how stable a preparation remains over time, and how the body responds to repeated exposure.

Alcohol has historically been used as a primary extraction medium because it reliably draws a broad spectrum of medicinal constituents from plants, preserves those compounds without the need for additional stabilizers, and remains physiologically tolerable when used in small, controlled doses. When tinctures are taken as intended—measured in drops rather than servings—alcohol functions as a carrier, not as a recreational substance.

Vegetable glycerin, by contrast, has a narrower extraction range and introduces additional considerations related to metabolism, digestion, and microbial stability. While it can be appropriate for limited or short-term applications, its use as a primary carrier for daily medicinal extracts requires careful evaluation rather than assumption.

From an educational perspective, “no compromise” does not mean rejecting modern tools outright. It means recognizing that each choice in medicine carries consequences, and that long-term healing is best supported by preparations that minimize unintended physiological burden while maximizing therapeutic clarity.

For those approaching herbal medicine with the view that the body is not a testing ground but a system worthy of care and restraint, these distinctions are not philosophical abstractions. They are practical considerations that shape outcomes over time.

References & Further Reading

-

Herb Pharm. (n.d.). The difference between glycerin and alcohol in herbal extracts.

https://www.herb-pharm.com/blogs/ask-an-herbalist/the-difference-between-glycerin-and-alcohol-in-herbal-extracts -

Mottillo, E. P., et al. (2022). Glycerol metabolism and its role in glucose homeostasis.

Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 961184.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9611849/ -

European Medicines Agency. (2017). Assessment report on glycerol.

https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/glycerol_en.pdf -

Aromatools. (n.d.). Alcohol-free glycerin extracts: Uses and limitations.

https://aromatools.com/blogs/aromatools-essential-ideas/alcohol-free-glycerin-extracts -

Wikipedia contributors. (2024). Glycerite. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glycerite -

Lin, E. C. C. (1977). Glycerol utilization and its regulation in mammals.

Annual Review of Biochemistry, 46, 765–795.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.003553